From

Benneckenstein to the World of Carnivores

The world of carnivorous plants is the world of

Siegfried and Irmgard Hartmeyer. The couple has traveled to the remotest

regions with their camera equipment, mostly tracking those plant genera which

evolution has endowed with a special appetite for animal protein.

A fleeting encounter almost 45 years ago with a

round-leaved sundew and a Venus flytrap has become a lifelong passion. Today,

the Hartmeyers are networked worldwide with carnivorous plant specialists and experiment not

only in their own greenhouse with microscopes, tweezers and cameras. Because of

their private films and research results, they have been invited to give video

lectures for instance to groups of prominent scientists in Japan and the USA.

In addition, there were joint research projects

and scientific publications. For example, they have done work with the bionics scientists

of the University of Freiburg, where investigations with a high-speed camera

and electron microscope described a new type of trap. This was the rapid

catapult-flypaper trap that disproved the myth all prey capture movements in Drosera are rather slow. If this was not

enough, one sundew discovered by them in Australia even bears their name: Drosera

hartmeyerorum Schlauer.

NWZ

regular

readers will probably be familiar with these carnivorous specialists because of

several reports. To all other readers, today's interview should be preceded by

a short personal note.

|

Siegfried

Hartmeyer was born in Hasselfelde in 1953 because the planned home birth in

Benneckenstein's Unterbruch 1 had to be moved to the hospital there at short

notice - the Midwife had fled to the West of Germany overnight. He spent the

first years of his childhood in Benneckenstein, before the unlawful

expropriation of the Hartmeyer family business that forced his parents to leave

home for West Germany. Professionally, things went well for him as a laboratory

groups director and plant fireman in the gas measuring group in the analytics

department of a Swiss chemical company. Despite all his geographical

remoteness, Siegfried Hartmeyer always remained connected with the Harz region.

From the mid-1960s until today, kinship ties have led to many visits to the old

homeland and ultimately to the circle of the Benneckenstein Culture and

Heritage Society. Also the collaboration on the biographical book of his mother

Christa Hartmeyer "Gezeitenwechsel im Hochharz" (translated “Changing

Tides in the Upper Harz Mountains”) provided a strong connection. Today we want

to ask him what special features he has encountered in his greenhouse over the

years.

Photo: Christa Hartmeyer with her book "Gezeitenwechsel im Hochharz" (Photo supplemented). |

|

Mr.

Hartmeyer, what actually fascinates you so much about carnivorous plants, which

you also like to call "Fleischis"?

And: Do you have any favorites

among the nearly 1,000 known species?

|

|

I am particularly interested in the highly effective

animal traps of carnivorous plants, which give botanists and others the

impression of ingenious evolutionary engineering, that is the biomechanics, or

bionics for short. For example at the University of Freiburg studies snapping, catapulting

or sucking carnivorous plant traps with latest analytical equipment, engineers

are already transforming these into advanced and environmentally friendly

practical applications. Studies of the mechanism of the Venus flytrap Dionaea

muscipula, helped in the development of autonomously opening and closing

sunshade lamellas for the shading of buildings and stadiums. They are operated

without hinges, electricity or motors, using the mechanisms of the famous snap

traps, the targeted use of inner tensions of the material. When you see such

successes of bionics in practice, it is only then that one really understands

what fascinating mechanisms evolution has produced with the carnivore traps.

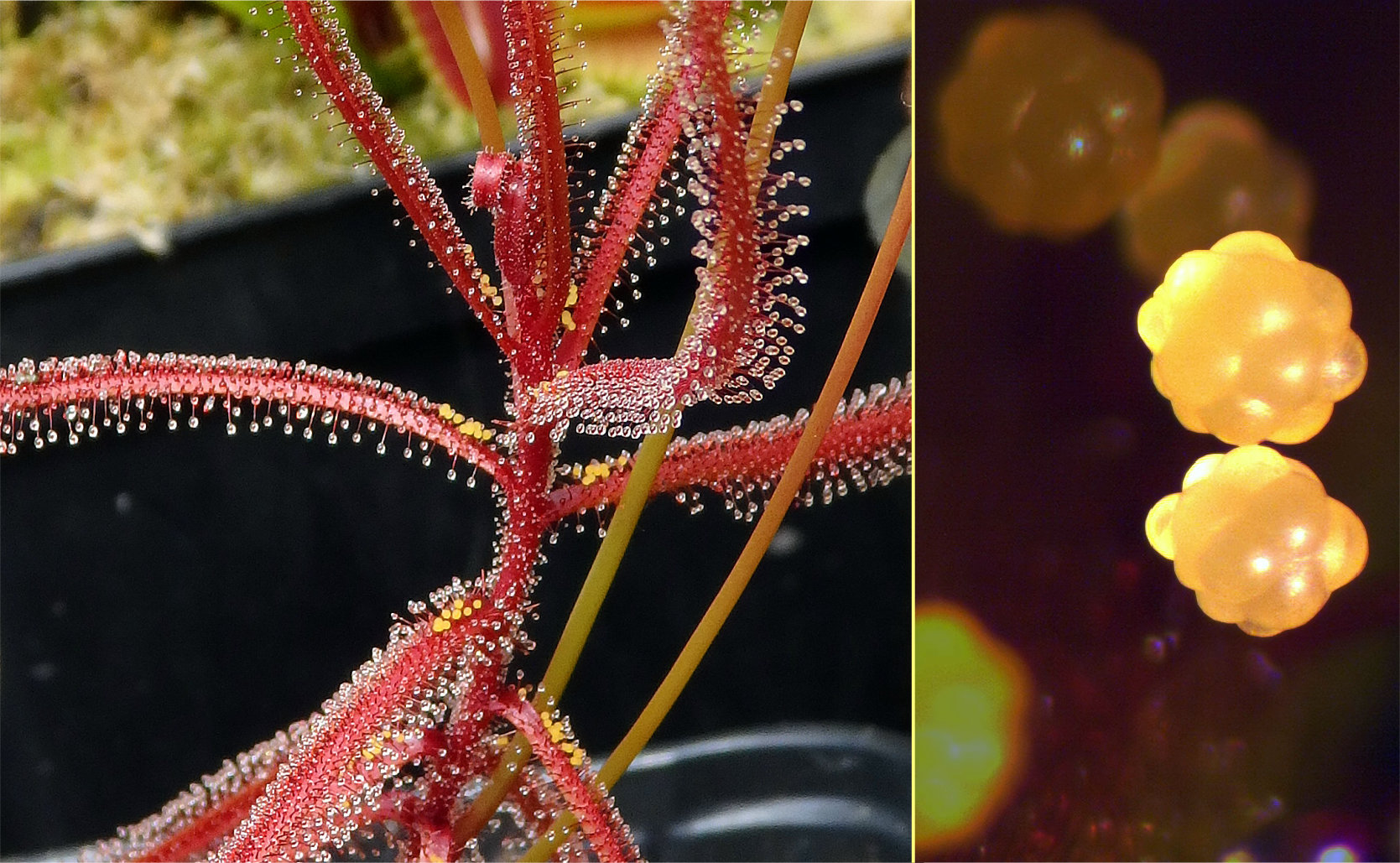

Among

my favorites among carnivores are the fast catapult traps of some sundews, especially

the the largest, Drosera glanduligera, in which our research played a

major role. It caused a lot of headaches. The plant was still considered

uncultivable in the early 2000s and it took us almost three years before we

were able to obtain reproducibly healthy adult plants for our experiments. The

truly sensational results show that the catapults of this sundew move at least

as fast as the Venus flytrap does.

The

article we published among others in the U.S. in 2010, was read by the bionics

team at the University of Freiburg, and probably because we were the only ones

who could provide healthy experimental plants, the current head of the Plant

Biomechanics Group, Dr. Simon Poppinga, invited us to join a joint research

project. In order to be allowed to experiment in the strictly secured

laboratories, Irmgard and I first had to sign 16 (!) declarations of secrecy.

The result of the following, very friendly cooperation was a publication in

2012 describing a new type of trapping, a combined catapult-flypaper trap. In

experiments, it hurls passing fruit flies with outstretched catapults (snap

tentacles) lying on the ground in sensational 75 thousandths of a second (ms)

onto their leaves, which have hairs covered with glue. This is much faster than

Dionaea which needs 100 ms for closing. The impact of the fly on the

leaf starts a kind of belt conveyor mechanism in the glue tentacles of the leaf

surface, which sinks the prey into a digestive cavity in one to two minutes, a

kind of stomach sack in the center of the leaf.

Even the well-known German science journalist Volker

Arzt asked by e-mail whether he could show the pictures of the fly-slinging

predatory plant, taken in our living room, for the first time on television in

the program "Planet Wissen". Of course, we gladly agreed. The report

was broadcast in 2015 and online until the end of 2020.

Photo: The Australian catapult-flypaper trap Drosera glanduligera flings passing animals into its glue tentacles in just 75 thousandths of a second (ms).

In the Guinness World Records 2021, it is now listed as "fastest terrestrial predatory plant".

|

|

From

when were carnivores actually described scientifically?

|

Carnivorous plants were first scientifically described

in the 18th century, not infrequently by the famous Carl von Linné, the

inventor of binary nomenclature, with the help of which science can name all

living beings by means of a genus and species name. However, even at that time,

he generally rejected the assumption that these plants were carnivorous, i.e.

they deliberately ate animals. He probably feared trouble from religious

authorities for such claims, similar to those experienced 100 years later by

Charles Darwin for suggesting carnivorous plants.

For Darwin this criticism was

not less massive than for his theory of evolution published 16 years

before. In 1875 Darwin published his famous experiments with sundew, etc. the

first scientific book, "Insectivorous Plants" in which, as the title

suggests, he clearly writes about insectivorous plants. Evangelical fanatics

saw the "divine order" endangered if plants were to eat animals

instead of the other way around.

Today, it is scientifically undisputed that

carnivores capture insects and digest them with enzymes, so Darwin was right.

We were even able to clearly prove in experiments that some sundew species

already starve to death as seedlings if they cannot catch enough food.

Left photo: Drosera aberrans „Maldon“ is a winter grower and stands the hot Australian summers dormant as a tuber, similar to our crocuses.

Right photo: Drosera capensis x aliciae

a beautiful hybrid from two South African species. After about 38

years, it is meanwhile the oldest sundew of the Hartmeyer collection.

|

|

How

does one get an invitation to Japan, for example, with such a hobby?

|

|

For the answer I must go a little further. Irmgard and

I spent since 1990 on three carefully prepared trips totaling of more than

seven months in Australia, where most species of carnivorous plants exist. The

motto for us was always "Take only photos, leave only footprints".

With small airplanes, helicopters and cross-country vehicles we searched and

filmed carnivores and a phenomena associated with them, sometimes accompanied

by local experts, but mostly as a team of two. We observed symbioses between

carnivorous plants and predatory bugs (Cyrtopeltis & Bybliphilus),

which can live completely unharmed and mutually beneficial in the midst of the

glue traps . In "Down Under", until our publication in an Australian

journal in 1996, such symbioses/mutualisms were only known from a rather

limited region about 3000 km south around the city of Perth.

In addition to our private investments in adventurous

excursions and better film equipment we had a good portion of luck. Irmgard and

I actually managed to film several undescribed symbiosis/mutualisms in northern

Australia. As the icing on the cake, we found an undescribed sundew in 1995,

whose transformed "tentacles" (emergences) reflect yellow light.

This was new in the genus Drosera.

In 2001,

after this plant suddenly appeared in Germany, we showed it to the

biochemist

and systematist Dr. Jan Schlauer, who was really electrified by our

find and immediately

started the scientific description of the new species. The reflective

emergences of "our" sundew and the newly found symbioses caused a

worldwide attention in expert circles. Nevertheless, I was astonished

when

suddenly the letter of a Prof. Kondo from Hiroshima University arrived

with the

words: "I would like to invite you to show a film lecture about your

discoveries in Australia in the context of the International

Carnivorous Plant

Conference 2002 at the Natural History Museum in Tokyo. In addition, I

would be

pleased if you could produce an official video about the

conference." This was such a great honor for us that we

immediately

booked the flights. The conference in English was a great success,

which

brought us many new worldwide contacts, friendships and follow-up

invitations.

Photo: The yellow light reflecting emergences (magnified on the right) of Drosera hartmeyerorum

lure insects into the deadly glue traps. This is only known from this species.

|

|

Have

you also experienced bizarre surprises in the greenhouse?

|

Oh yes, our mouse-eating pitcher plants Nepenthes

come to mind. Small vertebrates have been found in large pitchers in Borneo,

but it was surprising in our greenhouse. A total of five mice were caught by

two large plants in a few years, so this was not a one-time fluke. We would

never feed vertebrates to plants!

The mice came in unwanted, and we always

noticed it only by the typical stench near the trap, when digestion had already

started. In fact, the pitchers function like a real stomach with digestive

enzymes. For us of course it was an ideal opportunity to investigate how the plant

does this and what remains from such large prey.

The following probably took place: Attracted by the

sugar-containing excretions, which are produced by the nectar glands on the

underside of the lid, the mouse climbs up the rough outer surface of the pitcher

onto the sturdy "collar", the peristome, which surrounds the opening.

There it must stand up on two legs and bend slightly forward to lick the sweet

drops under the lid above her. Thereby a careless movement is enough, the rest

is done by gravity. The victim falls into the digestive fluid and drowns

without any chance of climbing the very smooth inner walls. Since all pitchers

remained completely undamaged after the capture, it was a proof that there was

no possibility for the rodents to bite through the walls.

The digestion of an adult mouse takes about six weeks.

When the trap was cut open, the remains were completely flattened and seemed

almost grown into the wall. So robust is the lower part of the pitcher that it

needed to be cut with a scalpel to remove the remains. Remaining were the fur,

hairs and gnawing teeth, as well as small remains of the most massive bones.

The rest of the body had been digested with enzymes and absorbed. The latter

could be seen by the fact that the following pitchers of the plant grew even

larger and stronger. As macabre as the pictures may be, our somewhat bizarre

article with the photos found great interest. Translations appeared in several countries;

even a large Indonesian garden magazine (Trubus) printed a report on it.

Upper left photo: As if the little mouth was still open in horror even in death.

The photo of this mouse caught in the trap of a Philippine Nepenthes truncata went around the world.

Upper right photo: The pitcher plant with two teeth,

Nepenthes bicalcarata from Borneo lives in symbiosis with ants

(Camponotus schmitzii), which hunt for prey by diving in the pitcher liquid. Smooth pitcher walls do not bother them.

Left photo: The sharp little teeth of this Nepenthes hamata from Sulawesi effectively prevent animals that have fallen into the pitcher from escaping.

|

Less bizarre, even dangerous turned out to be captures

in the greenhouse of the tropical tiger mosquito Aedes aegypti, which

immigrated only a few years ago, and which we discovered in the glue of our

sundews. They transmit dangerous diseases such as Zika, Chikungunya and dengue

fever. The Weiler Public Order Office had asked citizens to report findings of

the mosquitoes. They immediately sent a biologist to us, who confirmed that

they were indeed the tropical bloodsuckers. He gave me Culinex tablets,

with Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis with which the old branches of the Upper Rhine Valley are

treated every spring. It is only deadly for mosquito larvae. One hundred years

ago, our region was still a malaria area due to its mild climate and the transmitting

Anopheles mosquitoes are still present. A broth from the tablets is then

given into the water bowls in which our carnivores are standing, which are

unfortunately also ideal breeding sites for the invasive tiger mosquitoes. The

control is supported by our numerous sundew species in the greenhouse, for

which all the mosquitoes are ideal prey.

Photo: Hunting for dangerous tiger mosquitoes Aedes aegyptii, these Drosera serpens (left) and Drosera paradoxa

(both Australia) were successful in the greenhouse. This also helped to clearly identify the mosquitoes.

|

|

Are

you still currently involved in scientific projects on carnivorous plants?

|

|

This hobby has never been and will never be boring.

Since 2016 we have been cultivating certain sundew species in order to examine

them for their chemical constituents in collaboration with Dr. Jan Schlauer.

The so-called chemotaxonomy is quite helpful for both systematics and questions

about the evolution of the genus. Up to 2019, this resulted in several

scientific publications. All these articles can be found on our homepage.

Only last year, together with Prof. Stephen Williams

(USA), we were able to publish an article about experiments with ants in our

garden, which happened to have made a burrow right next to a group of Venus

flytraps and really walked permanently through the traps without triggering

them - A great coincidence. We succeeded in proving statistically that the

large snap traps allow small ants, which are unprofitable as prey, to escape in

a targeted manner by combining several ingenious features in order to save

energy. Of course, we have films of this, which can be seen on our YouTube

channel. In the meantime, more than 1.6 million views prove that they are of

interest.

But one more point on your question: Fortunately - you

will have guessed it - even during this interview, some laboratory equipment

runs analyzing our plant samples taken in 2020. Sown in April, we harvested

them at the beginning of October in the greenhouse and sent them by express to

a laboratory in Helsinki. It looks quite good so far; a new publication will be

released in 2021 at the latest, depending on the duration of the peer reviews it

will appear in a specialist journal.

Recently, we were surprised to receive an e-mail from

Dr. Poppinga from the University of Freiburg with great news: The

aforementioned catapult-flypaper trap has now been entered into the Guinness

Book of Records as the "fastest terrestrial predatory plant in the

world" with 75 thousandths of a second (ms) for a capture process, based

on our joint laboratory measurements.

(Photo supplemented: A happy celebration with

Guinness. The upper portraits show the Australian Richard Davion

(left), who found the catapult function and Dr Simon Poppinga, who

conducted the speed measurements together with the Hartmeyers at the

University of Freiburg (Germany). |

|

Six

years ago you combined a vacation in the Harz mountains with some excursions

through our Brocken moors. Accompanied by Brocken gardener Dr. Gunter Karste,

you were able to examine the sundew deposits there. You published your results

in a very interesting and not less entertaining video. Is there perhaps the

intention to repeat such an action again?

|

|

I have the best memories of the excursions with Dr.

Gunter Karste on the Brocken and surroundings. We saw, for the first time

butterworts (Pinguicula), sundew as well as some orchids (Dactylorhiza

species) at natural places in my old homeland. This was a great experience,

especially because the fascination for carnivorous plants in me was actually

caused by the round-leaved sundew D. rotundifolia. I have the best memories of the excursions with Dr.

Gunter Karste on the Brocken and surroundings. We saw, for the first time

butterworts (Pinguicula), sundew as well as some orchids (Dactylorhiza

species) at natural places in my old homeland. This was a great experience,

especially because the fascination for carnivorous plants in me was actually

caused by the round-leaved sundew D. rotundifolia.

I am still happy like crazy when I see this plant in

the nature in front of my camera. In addition there is also scientific

interest. As the only one of our native sundew species, D. rotundifolia

forms at different times either glue tentacles or completely dry snap

tentacles, similar to the ones of the Australian catapult traps, although not

quite as fast moving. Why there is this dimorphism here and what causes the

formation of the different tentacles in this species, I have not yet been able

to explain. I hope that it will happen one day. Our film “Fleischfresser auf

dem Blocksberg” (Translated "Carnivores on the Blocksberg"), which

also deals with our family history in Benneckenstein, can be watched free of

charge on our YouTube channel.

We have considered further excursions in the Brocken

area a few times since then. At the moment, however, we can't travel with my

89-year-old mother, who of course always accompanied us to Benneckenstein. For

health reasons we do not want to leave her alone for a long period in Corona

times. I am sure that we will go on tour in the Harz mountains again in the

future and we are looking forward to it!

Photo:Siggi and Irmgard Hartmeyer in their impressive

greenhouse full of hungry plant stomachs.

Jürgen Kohlrausch thanks you for the interview.

|

|